Lines That Matter: The Battle Over Rainbow Symbols in Public Spaces

Rainbow Symbols Are Under Threat—Communities Nationwide Are Fighting Back

Disclosures: More than 5 years ago, Will Fries provided communications training and advertising guidance to Jared Schablein.

You can read our previous story about rainbow crosswalk dynamics here: Salisbury, MD’s Anti-LGBTQ+ Actions Draw Transatlantic Criticism

Across the United States, symbols of inclusion and safety, from rainbow crosswalks to bridges and Pride flags, are being reexamined and challenged. Some officials cite neutrality and safety, but many see a deeper pattern: a quiet rollback of inclusion cloaked in bureaucratic doublespeak. In Salisbury, Maryland, a plan to remove the state’s first rainbow crosswalk has sparked fierce backlash and international attention. But this is not just a local dispute. It is part of a broader reckoning over who belongs in public space and what happens when governments retreat from the values they once publicly embraced.

Salisbury’s experience illustrates how the language of neutrality can be used to obscure deeply political decisions. The City now says its plan to paint over Maryland’s first rainbow crossing is “on hold” following intense public criticism. While officials claim no final decision has been made, residents and advocates view the delay as a sign of institutional hesitation, not genuine reconsideration. The controversy has become a inflection point in a wider national debate over symbols, safety, and selective inclusion.

Installed in 2018 at the intersection of South Division and Market Streets, the rainbow crosswalk has come to symbolize visibility, resilience, and belonging for LGBTQ+ residents, the broader public, and visitors alike. Then-Mayor Jake Day championed the initiative, with the participation of Salisbury PFLAG, as a historic first for the state and a milestone in Salisbury’s growing reputation as a welcoming and inclusive economic powerhouse on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Rainbow crosswalks are not political symbols but affirmations of community inclusion. They are strongly associated with the LGBTQ+ community because of their long history being excluded through mechanisms of discrimination, corruption, and violence.

In 2024, the City’s message shifted. Mayor Randy Taylor, elected the previous year, started making vague but persistent remarks about removing the crosswalk. He framed the design’s association with the LGBTQ+ community as a political message. Speaking to WMDT in July 2024, Taylor said, “It has everything to do with fairness, and staying neutral and supporting everyone, not just a singular group,” adding, “We as a city, we have gotten ourselves, where we adopted, I think an inappropriate level of connection with a particular group, that is somewhat political in nature.”

In May 2025, those statements took shape as policy with the announcement of the “Crosswalk Canvas” program, a public art initiative targeting the specific intersection featuring the rainbow crosswalk. During the rollout, Taylor again emphasized neutrality, telling WMDT, “We want our public spaces to be welcoming to all. However, we also have a responsibility to ensure that government property remains neutral and does not promote any particular movement or cause.”

Critics argue the city is deliberately and intentionally making anti-lgbtq moves to reverse Salisbury’s past inclusionary stance. They say the program’s framing reinforces a false equivalence between inclusion and partisanship, one that dismisses the lived realities of marginalized communities.

The pushback has been swift. Local residents, elected officials, civil rights groups, and international observers have condemned the city’s move. Despite public testimony and a recommendation from Salisbury’s own Human Rights Advisory Committee urging officials to preserve the crosswalk, the city appeared poised to proceed with the redesign. Now, after multiple rounds of scrutiny, Salisbury Communications Director Victoria Idoni, who joined the city after the program’s launch, has shared with The Watershed Observer that “the entire project is currently on hold.” She also describes the city’s original motivation as wanting “to do something new with the space,” a noticeable shift from Taylor’s earlier justifications.

That evolving narrative has drawn renewed attention, especially in light of a federal memo issued in July by U.S. Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy. In a letter to state governors, Duffy urged local governments to eliminate “distractions” from crosswalks as part of a national traffic safety initiative known as SAFE ROADS.

“We’re getting back to the basics,” Duffy wrote, calling for a return to uniform crosswalk designs that are “standardized and free of unnecessary markings.”

Though the memo itself makes no explicit reference to LGBTQ+ symbols, the Secretary has made other comments including social media posts criticizing the rainbow crosswalks.

Local civic leaders have responded.

Maryland State Delegate and Wicomico County Republican Central Committee member Barry Beachamp questions the city’s priorities, “if there is excess money in the budget, I would like to see the focus more on potholes,” he said. And later he added, “When you’re in office, you should serve everybody.”

Hanson Egerland of Eastern Shore Organizers shared, “Recently, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy issued a statement saying that all of the re-painted crosswalks across the country are actually all of a sudden a problem. This type of reactionary regression is to be expected. It must be met with community voices to push back.”

Jared Schablein of Shore Progress says, “We oppose all of Mayor Taylor’s efforts to remove it. Our city should focus on affordable housing, attracting good-paying jobs, and ensuring our community is safe for everyone who calls Salisbury home, not on culture wars.”

As the community crosswalk’s fate remains insecure, one thing is clear: the conversation is no longer just about paint on pavement.

As the debate around the crosswalk continues to unfold, more community voices are emerging to shape what’s next, for the intersection itself, and for the values it represents. Here are a few of those voices from Maryland, Wisconsin, Florida, and Virginia:

Local NAACP Leader: Inclusion Must Be Backed by Action, Not Just Rhetoric

“I think one of the things that we need to do is open our minds and have some humanity. Kindness goes a long way.” - Monica Brooks, President of the Wicomico County NAACP

For Monica Brooks, president of the Wicomico County NAACP, the City’s poor judgement about Salisbury’s rainbow crosswalk reflects something deeper than public art policy. It signals a broader pattern of discrimination, exclusion, and misaligned priorities that have long shaped the region’s governance.

“It’s been looking like there’s a concerted effort to make certain people feel welcome. At the same time, it looks to me like there’s also an effort to make a lot of people feel not welcome and that includes people of color.”

Adding, “There have been microaggressions that have been occurring throughout the city that I find to be really unnecessary.”

Brooks, who has attended more council meetings than she can count, says she’s seen this dynamic play out before. She’s not surprised that the city found funding to paint over a crosswalk while struggling to address homelessness or basic infrastructure. “You’re talking about a city that is talking about increasing taxes and not having funds for this, not having funds for that but somehow, some way, miraculously we have funding to paint over crosswalks,” she said. “Something’s wrong with that picture.”

For her, the issue isn’t just about symbolism; it’s about the city’s values, and what rises to the level of priority. Brooks pointed to the city council's focus on what she called “low-hanging fruit,” like abandoned shopping carts legislation while larger crises remain unresolved. “How does that become what we focus on,” she asked, “when we have a huge portion of our community that is growing every day that are unhoused?”

That disconnect, she said, reflects the limits of a system where those in power don’t reflect the diversity of the community they serve. “Salisbury’s diversity is increasing day by day,” Brooks noted. “Yet our government has not reflected that.” While she acknowledged diversity on the city council, she was blunt about the broader staffing dynamics: “The City of Salisbury government continues to be 90% white.”

In the context of discussing leaders who look to marginalized groups for leadership on the issues most important to them she says, “to me that is a very ignorant.”

Representation matters, Brooks emphasized, and not just in appearances, but for shaping policy and outcomes. “If you’re an elected official, then you have a level of power and influence to determine what happens and who it happens to,” she said. And when leaders hire others who “don’t have a clue” about the communities most impacted, she says those voices go unheard and those needs unmet.

Brooks can speak with authority about what legal discrimination looks like locally. Earlier this year, under her leadership, the Wicomico NAACP won a landmark lawsuit challenging the county’s racially discriminatory voting districts. According to Brooks, it was the second major intervention in local governance: the first came in the 1980s, when the threat of legal action forced reforms to allow a single Black representative. This time, it took a court battle to move beyond that.

The victory, Brooks said, was about more than district lines; it was about refusing to let a small fraction of people speak for an entire community. “We sued so that we could get fairness and equity here,” she said, “so that we could get better representation throughout every neighborhood.”

Still, legal wins are only one piece of the puzzle. To build lasting change, she believes Salisbury needs leaders who are curious, courageous, and willing to expand their scope of engagement. That means getting out of comfort zones, showing up in unfamiliar communities, and being intentional about listening not just when it’s convenient.

“If all the folks you interact with are from your same background and same experience, then you’re leaving out a whole group,” Brooks said. “You’ve got to be willing to knock on doors, put out surveys, and actually ask people what they’re dealing with. Don’t just make assumptions. Get real data.”

“If you don't want to get to know who we are then that's a problem,“ she added.

She described leadership as not just positional power, but relational commitment. The most effective leaders, she argued, are those who create a sense of welcome, where community members feel safe reaching out, even when the answer might be no. “Even if there’s nothing they can do about the matter,” she said, “being willing to listen goes a long way.”

That spirit of listening, she added, is essential not just for governance, but for community. “Take the opportunity to get to know people you’re not familiar with,” she said. “Hear about what they’re going through. If I’m in a community and something awful happens to someone, that should prick my heart. That should give me a desire to help.”

When that empathy is absent or worse, when leaders appear indifferent or dismissive, Brooks said the consequences will be real. “You encounter people who just don’t want to hear from you,” she said. “They don’t care that people are dealing with these things. They don’t care, they think it’s not their problem. Or they want to belittle. But we are mighty.”

She spoke proudly of the NAACP’s ongoing efforts to organize, educate, and advocate across Wicomico County. “We do great things for our community, and we are a collaboration of volunteers,” she said. “We’re not getting paid for this work. We do it out of love.”

Then adding, “we always welcome people to join the work that we do to make this community more equitable and yes, we take people of all races to be a part of this work.”

She wants people to know the organization welcomes new members of all races and backgrounds and holds public meetings on the fourth Thursday of every month. “This organization was founded in diversity, and we continue to push for diversity,” Brooks said. Their Facebook page is https://www.facebook.com/people/NAACP-Wicomico-County-7028B/61574194925496/ and those interested in getting involved are invited to contact her directly via email at president.wcnaacp7028 at gmail.com.

Wisconsin State Rep. Rivera-Wagner says 'We’re Not Going Back'

“No national administration can tell us that we have to go back into closets and into hiding. So I think it’s time that we stand up and fight back.” - Wisconsin State Rep. Amaad Rivera-Wagner

In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a new rainbow crosswalk is about to take shape in the city’s historic Walker’s Point neighborhood. It’s part of the “Paint the Pavement” initiative, a city-backed effort to uplift artists and transform public infrastructure into storytelling platforms across the city. The new design, created by internationally recognized queer street artist Jeremy Novy, is more than decoration. For State Rep. Amaad Rivera-Wagner, it’s a public affirmation of presence, history, and resilience.

“We were really hoping to increase LGBTQ visibility and voices to make sure that we have historical markers that capture that history and those contributions,” Rivera-Wagner said, reflecting on the project’s purpose. The first openly gay man of color ever elected in Wisconsin, Rivera-Wagner also serves on the board of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project, a group working to preserve the state’s queer legacy including events like the 1961 Black Nite Uprising, one of the earliest recorded queer-led acts of resistance in the country.

“In this moment, even something as simple as a crosswalk or a plaque feels like a radical act,” Rivera-Wagner said. “Given the national consequences of erasing, silencing and at its worst taking away fundamental rights and dignity, these small symbols carry a big impact.”

The new rainbow crosswalks are intended not just as celebratory installations, but as counters to what Rivera-Wagner and many others see as a growing tide of erasure. “It’s paramount that we rally together to preserve the stories that are part of the beautiful fabric of how we got here. How we’ve always been here. And how we contribute to communities.” He added, “We should be pushing back on any of those kinds of repressions, it’s time for community to stand up.”

That commitment to memory and visibility, he says, is especially urgent now, as federal officials like Sean Duffy invoke neutrality and safety to discourage colorful or symbolic crosswalks. “I would hope at this point in 2025, different colors on a pedestrian crosswalk would not cause any issues,” Rivera-Wagner said. “But it wouldn’t surprise me if an administration tried to make an issue out of nothing to stoke a culture war and target people like the LGBTQ community.”

The city of Milwaukee’s response has been the opposite of Salisbury’s. Rather than back away from symbolism, officials are investing in it. “We’re tapping into an ongoing effort to create really cool artist projects in crosswalks,” Rivera-Wagner said. “To me, that’s what shared public space should do: tell all our stories. Not just one group’s.”

He sees the current climate as a test, not just of policy, but of will. “We all have shared histories and truths. One of the ways we build community is by telling the different stories of how people arrive, how they show up, and how they contribute. The LGBTQ community is part of that story.”

“I think anyone who is trying to bully an already vulnerable population to try to divide our communities should be held accountable,” he said.

For Rivera-Wagner, the tension isn’t new. He notes that the very spaces LGBTQ people have carved out have long existed under threat. “We created spaces of love and joy and community,” he said, “but it was often in the context of an oppressive larger society or state that didn’t want us to be visible and wanted us excluded from the rights and privileges associated with humanity.”

That’s why preserving symbols like crosswalks matters, he says, not just as a celebration, but as a confrontation with history. “We cannot build a future without looking back at the full picture. Not everything was perfect. That exclusion could be violent, and the pushback could be violent. But acknowledging that is how we avoid repeating it.”

“I don’t know if history repeats itself, but it does rhyme,” he said. “We’re seeing that in real time at the national level. We need to be more aware of our history so it rhymes less.”

Despite the mounting challenges, Rivera-Wagner remains hopeful. “When I came out, the idea of marrying the person I love was called a fantasy. But we fought and we won. So yes, I think this is a dark turn for LGBTQ rights. But I also think this community is powerful and resilient.”

He wants communities around Wisconsin, the nation, and the world to know one thing about LGBTQ+ rights and visibility, “We’re not going back.”

Florida’s Wilton Manors’ Rainbow Bridge Faces Its Own Battle

“There is zero evidence to support the argument that rainbow markings are unsafe. In fact, there’s a lot of evidence they improve safety.” - Chris Caputo, Vice Mayor of Wilton Manors

In Wilton Manors, Florida, a city known for its vibrant LGBTQ+ community, the rainbow bridge has become both a cherished landmark and a flashpoint in the state’s ongoing efforts to restrict queer visibility.

Vice Mayor Chris Caputo, described the painstaking process of getting the bridge marked, a journey spanning two to three years of negotiations with state authorities. That effort now faces strange accusations amid Florida’s recent legislation targeting traffic markings, a law Caputo described as “a bit questionable.”

Still, Wilton Manors is pushing back. Caputo acknowledges that the rainbow bridge is not a traffic marking and that the new Florida law should not apply.

“There’s never been a single published study, and I’ve looked at more than 25, that shows rainbow crosswalks or similar markings make things less safe,” he said. According to Caputo, all studies he’s reviewed indicate the opposite: such markings actually improve traffic safety.

Caputo explained the irony behind safety arguments used by opponents: “Whenever people say it’s unsafe, it’s always subjective. Someone will say, ‘I was driving, and the colors caught my eye,’ and they leap to the conclusion that it's unsafe. But that attention is what makes it safer: people slow down, pay more attention, and as a result, traffic incidents go down.”

He pointed to Tallahassee, Florida’s capital, which also has a rainbow crosswalk. “The data there confirms a reduction in traffic safety incidents,” Caputo noted. “So it’s fascinating that the governor is pushing an agenda that’s anti-LGBTQ, even when the facts show these markings improve safety.”

Beyond safety, the rainbow bridge carries deep symbolic meaning. Caputo said it signals to visitors and residents alike that they are welcome in Wilton Manors and that the city embraces its full community. “Without a doubt, for people coming into Wilton Manors, you see the rainbow bridge and you know you matter. You feel welcome.”

He drew parallels to Orlando’s Pulse nightclub memorial crosswalk, underscoring the power of public art to honor lives and affirm belonging.

“You have a crosswalk that makes things safer, yet there’s pressure to erase LGBTQ visibility and, at the same time, potentially make traffic crossings less safe, an outcome that could lead to more loss of life.” says Caputo, while acknowledging that officials who ignore realities like safety data open themselves up to potential liabilities.

For advocates like Caputo, the fight extends beyond city limits. “We have to push back on many fronts. There’s the human front, where people relate to respect and dignity, but that conversation doesn’t always work with some on the political spectrum.”

Instead, he said, “we have to be smarter,” armed with facts. “There is zero evidence to support the argument that rainbow markings are unsafe. In fact, there’s a lot of evidence they improve safety.”

Leesburg, Virginia: A Crosswalk That Signals Everyone Belongs

“Our symbols represent people, not political ideals, but who we all are as human beings worthy of equality, love, and belonging.” - Candice Tuck of Equality Loudoun and Loudoun Pride Festival

In Leesburg, Virginia, the rainbow crosswalk is more than a colorful stretch of pavement. It is a deliberate statement of inclusion and a visible beacon of hope for a community that has long strived for acceptance. Candice Tuck, a leader with Equality Loudoun and the Loudoun Pride Festival, has helped lead that effort.

“Equality Loudoun was founded in 2003 to create spaces where LGBTQ community members could gather, find support, and build a sense of belonging,” Tuck explained. More than two decades later, the organization’s mission has evolved but remains centered on fostering acceptance and the shared values of love and inclusion.

Still, Tuck said the most important part of her life is not her activism. “I’m a mom. My priority when I get up isn’t advocacy, it’s getting my two kids off to school.” She sees activism as a community responsibility to help neighbors who are struggling and the world doesn’t understand very well find a sense of respect, justice, and dignity.

The inspiration for Leesburg’s rainbow crosswalk came during a family trip to Washington, D.C. “My daughter was about 11 years old, questioning her identity, and when we saw a rainbow crosswalk, I knew immediately it would be an incredible symbol for families like mine,” Tuck said. “It says, ‘You do belong here.’ As clear as the colors on the pavement. That message lasts.”

For Tuck’s family, the crosswalk is part of everyday life. They often pass it on their way to a nearby ice cream shop.

According to Tuck, Leesburg’s public works department reviewed the common safety concerns raised about rainbow markings and found no evidence they pose a risk. “All the research shows that rainbow crosswalks improve pedestrian visibility,” Tuck said. “Crosswalks aren’t meant to be ignored. They’re meant to be seen and respected. Any so-called distraction is actually a positive one because it causes drivers to slow down and pay attention.”

Beyond traffic safety, the crosswalk communicates community values. “It proclaims that this county is a place of tolerance,” Tuck said. “We won’t tolerate the actions and rhetoric of hate and intolerance that are rising in other places.”

She explained that the rainbow design reflects more than LGBTQ+ identities alone. “It’s not just about people’s orientations or identities,” she said. “The queer community is the largest cross-cultural community in the world. We exist in every religion, every country, every social and economic class. Our crosswalk incorporates brown, black, and white stripes because this is about all issues: human dignity, respect, and acceptance.”

Tuck criticized efforts to politicize LGBTQ+ symbols. “We’re seeing attempts to misunderstand the purpose of these symbols or to politicize people’s identities,” she said. “I think people in the queer community are trying to do the best we can in a world that’s already working against them in almost every way imaginable.”

To communities considering similar efforts, she offered practical advice. “Research the legal and safety requirements. Understand who owns the roads and the approval processes. We were fortunate to have advocates who guided us through that.”

Reflecting on the ongoing challenges facing LGBTQ+ communities, Tuck called for deeper connection and education. “My biggest hope is that people take the time to really meet and understand us—not just Google or ask ChatGPT, but to have conversations,” she said. “I’m always willing to sit down for coffee and talk. These aren’t political issues to me. They affect my safety and my ability to care for my kids.”

Tuck’s story is a reminder that the fight for rainbow crosswalks is not just about symbolism. It is about human dignity and belonging. It is about everyone’s right to live openly and safely.

Maryland Political Analyst Weighs In: Citizens Must Lead the Charge

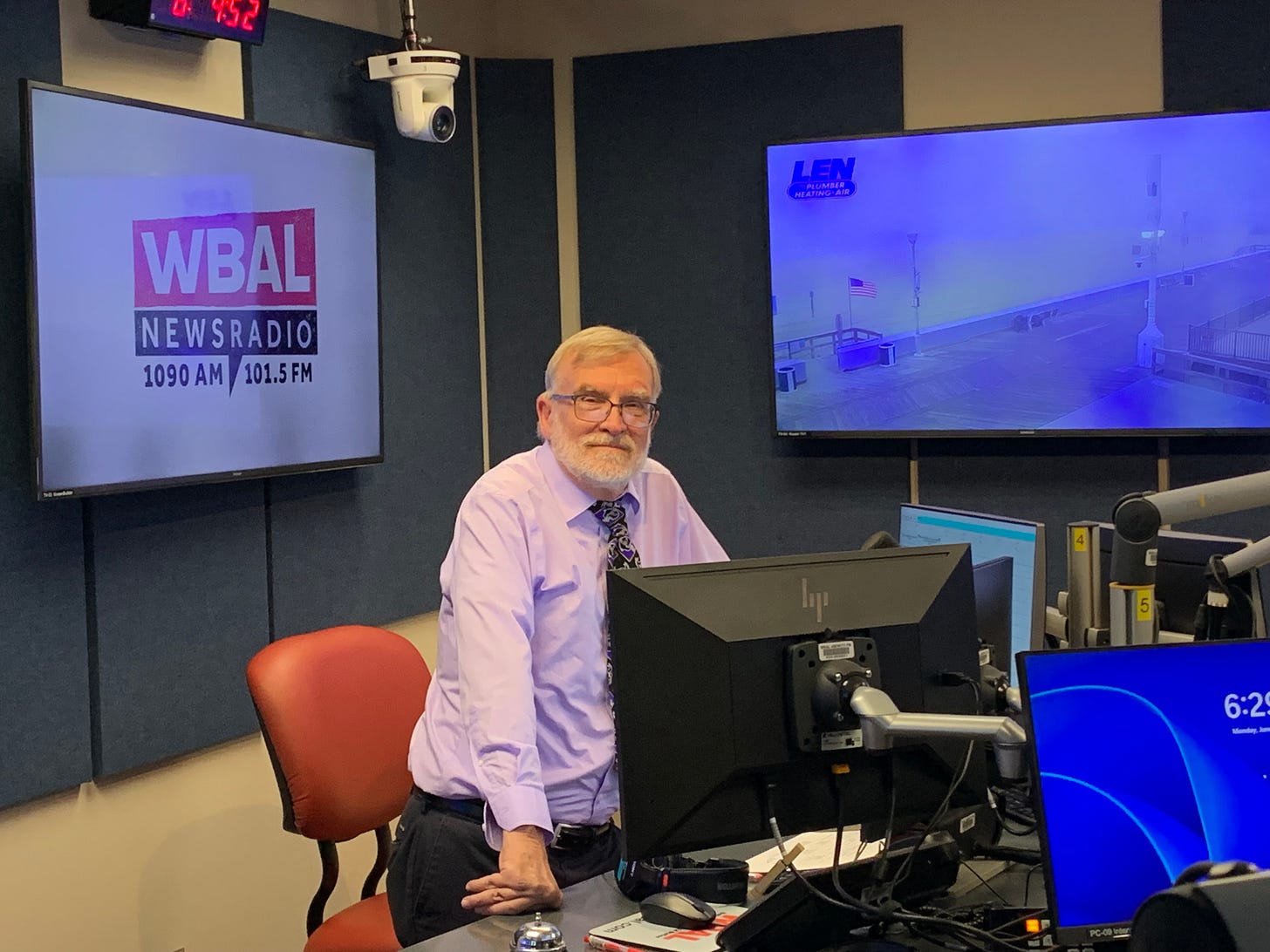

“I think the leadership has to come from citizens.” - John Dedie, Political Scientist

John Dedie, a political science professor at the Community College of Baltimore County and media personality who writes on Maryland politics, sees Salisbury’s crosswalk controversy as part of a broader pattern. “I think it’s up to the citizens in many ways to call out the government on the back slide,” Dedie said, “and I think sometimes you see slides like this when you see how the national government reacts to certain things.”

He pointed to history as a lesson on hidden signals in politics. “In 1981, it was the PATCO strike for the air traffic controllers, and everyone said, ‘Well, what’s the big deal?’ Reagan fired them, but that was a hidden message sent to the business community.” Dedie notes that Regan’s signal communicated to businesses that his adminstration would not protect or stand up for unions. Dedie further explains that actions like refusing to fly the pride flag and threatening to remove rainbow crosswalks can be interpreted as similar signals to others in communities encouraging them target the LGBTQ+ community with further discrimination, corruption, or even violence.

Dedie also offered insight into the city council’s failure to formally codify the rainbow crosswalk and flying of the pride flag. “When people ask, ‘Well, why didn’t you codify it?’ the answer from elected officials may be, ‘Well, we just always thought it would be there.’ They made an assumption and they took it for granted.”

For Dedie, the path forward demands active citizen leadership. “I think the leadership has to come from citizens, and you can start with basically saying, ‘I want to sit down with someone. I want to sit down with local government and explain why this is important.’”

He also encourages communities to bring in allies beyond the immediate LGBTQ+ community. “You could bring in people who are not part of that community to come support business and things like that. Show that there are economic advantages to these things.”

If elected leaders dismiss community concerns, Dedie urges residents to leverage their voting power and economic influence. “I think citizens have to use their advantages they have as voters and remind leaders that, ‘You may not like this, but we have the power of the vote.’ I think you use that and also power the pocketbook.”

He advises people to remain engaged and foster dialogue. “My guidance for people is to make it clear that citizens have to be active, sit and talk with other people and show them the advantages of these types of things. That’s how you build community, and when you have a strong community like that, it creates an open and welcoming environment.”

Dedie highlights how demographic and economic shifts reshape communities. “The reason those communities change sometimes is demographic. I mean, 30 years ago, Frederick County used to be called Fredneck because it was considered a redneck area.”

“But what happened is housing became more expensive in the state of Maryland, more people expanded out and they started to move to Frederick County, and they brought their Montgomery County and liberal values to a very conservative area. Frederick has changed over time.”

Finally, he was reminded of the powerful role economics plays in civil rights movements. “Martin Luther King led protests that included economic boycotts,” Dedie said, “because no one discriminates against the color green.”

Julie Peters: Undoing Progress Is Problematic

“I have a problem with people wanting to undo progress.“ - Julie Peters, Mother, Human Rights Advocate, PR Professional

Julie Peters is not just a mother and public relations expert, she’s also a member of Salisbury’s Human Rights Advisory Committee. She says the threats to remove the rainbow crosswalk make her “sad” and “concerned.”

She describes how the rollback of visible symbols like the rainbow crosswalk hasn’t just been symbolic. It’s personal. Her family has begun to question how safe it is to speak freely in public. “It’s been hard for me to see things that are valuable to my daughter, as a sign of ‘I matter in this community,’ be stripped away to the point where she doesn’t feel like she’s safe in this community.”

As someone with experience in both human rights advocacy and public relations, Peters sees an unmistakable pattern. “I have a problem with people wanting to undo progress,” she says. “Because to undo what so many have come to celebrate and embrace and enjoy about living in Salisbury is hurtful. It’s hurtful to the people that that meant something to. And I don’t recall there ever being a public outcry that we take away the rainbow crosswalk. I don’t recall there ever being people who are signing a petition to have it covered up.”

She’s especially critical of how the city framed the crosswalk’s removal as part of a new public art initiative. “The fact that they’re trying to make it like an arts competition—they could have done that elsewhere in the city,” she says. “It didn’t have to be that particular crosswalk. So I think that trying to reframe doing away with the crosswalk as a new public art initiative is perhaps not entirely truthful.”

That sleight-of-hand, she says, is part of a broader problem with how inclusion is treated more like a seasonal obligation than a year-round commitment. “It shouldn’t be something that you’re just doing in the month of June,” she says. “It should be year-round. You know, putting out materials that have more photos than just white heterosexual couples. Putting out information that is inclusive to our immigrants, our LGBTQ population, and all of the other disenfranchised folks.” Pride Month, she adds, should not be the whole show. “Let Pride Month be the month that you shine a spotlight on what you’re doing but do it all year long if you really want your entire community to feel embraced and appreciated and included. If you were inclusive all year long, I think the benefits would pay off far more than some people getting upset with you in the month of June.”

Peters also wants it clearly understood that the Human Rights Advisory Committee advised the city to keep the rainbow crosswalk. “Yes. We very strongly urged him to keep it,” she says, referring to the Mayor. “We cited that it was a historic landmark, essentially, because it was the first one in the state of Maryland. If for no other reason, we think it’s worth preserving just because of that. But mainly, it’s because it meant a lot to the people here. The people who are in the community that the crosswalk represents, it was very meaningful to them to feel accepted and included. And now it’s just being done away with.”

After the Human Rights Committee met with the Mayor, Peters says there was a temporary pause on the removal. But when the city later moved forward with its “canvas crosswalk” plan, the media coverage created a false impression. “WBOC did a piece and said that we had advised him. But they didn’t say that we advised him to keep it, so it made it look as if the committee had endorsed his decision to undo it. And that was not true at all.”

She’s also frustrated with the City Council’s perceived inaction. “It’s frustrating. It’s difficult to have an issue where a significant amount of the population is very concerned about something and wants it to change and the government appears as though they’re not doing anything about it. Action would definitely be preferable.”

If she could say something directly to the Council, it would be simple: “I would love the city to be able to preserve the crosswalk. That would be my preference, because it is historic, and at this point, significant.”

To Salisbury’s LGBTQ+ residents, Peters offers this: “I want them to know that they do have allies. That there are people in Salisbury and groups in Salisbury that are very open and inclusive and want to help and want to advocate for them. So I would say, make your voice known. Reach out to the City Council. And look for those allies. Look for the people that will stand with you and speak out on your behalf.”

To others in the community who may feel uncertain or reluctant to get involved, she urges a shift in perspective. “I mean, the bottom line is, they’re people. And so it’s no different than being concerned about your neighbor or being concerned about your coworker. Sometimes, just being available to listen is enough. But recognize the struggle someone is facing. We all have struggles. The most fortunate of us are not having a struggle that’s based on our identity—who we are. It’s more like, ‘Oh, work sucks,’ or ‘I have a health issue.’ It’s not ‘who I am is not accepted in the community.’”

Her message to the broader Salisbury community is one of empathy. “Just think about it. At the end of the day, it’s a person. It’s a human being. Be kind, be open. Don’t come at a person with judgment right off the bat. Get to know them. Talk to them. Find out what they’re dealing with. And show empathy.”

Peters also shared the words of her daughter and wanted to be sure her voice was part of this conversation. “She said the importance of support shouldn’t be seasonal,” Peters recalled. “She did talk about the federal government erasing queer history from government websites—with the Stonewall Monument—which is very offensive, to say the least. And she said, ‘Including queer people in the conversation is paramount. I would expand on amplifying LGBTQ voices.’”

No Such Thing as Neutral: A Scholar Unpacks the Politics of Erasure

“Just putting up a flag doesn’t solve structural injustice, but it starts by saying, ‘I see you.’ That may be the beginning.” - Professor Kosta Kyriacopoulos, Salisbury University

For Professor Kosta Kyriacopoulos, a father and professor of multicultural education at Salisbury University with training in Queer Theory and Feminist Studies, the fight over the city’s rainbow crosswalk is not just about paint or process; it’s about power, and the stories cities tell about who gets to belong.

“One of the persistent issues that comes up when people ask whether we’re anti-LGBTQ+ is this idea of neutrality,” he said. But neutrality, he argues, is not some natural baseline. It is culturally embedded, shaped by dominant narratives of who and what counts as acceptable. “There’s no doubt that we are definitely anti-LGBTQ+ across the board,” he said about the City of Salisbury. “Neutrality suggests a default culture. But there is no neutral.”

He sees that posture playing out in local decisions, especially in the city’s refusal to codify visible support for LGBTQ+ communities. “You are either in favor of recognizing people as people, or you are not,” he said. “And if you are not, then you are anti. You are saying they don’t get a right.”

Some of Kyriacopoulos’s research has focused on what he calls “methods of silencing,” which, he explains, often come dressed as civility. “Calls for civility, politeness, neutrality—these are efforts to say, ‘just don’t bring that up.’ When people walk around with flags or crosses and talk about neutrality, that’s not neutral. That’s dominance masked as objectivity.”

He finds it especially dangerous when erasure is framed as inclusivity. “The more deeply concerning aspect is the neglect of identity. Removing Pride flags or rainbow symbols under the guise of fairness or uniformity isn’t equal treatment. It’s censorship,” he said. “You erase people, and then you pretend they never existed.”

That erasure is not just symbolic. Kyriacopoulos cites alarming statistics from Salisbury. “We know for a fact that in this city, if a child comes out as transgender, one in two are likely to be thrown out of the home. That’s devastating. There is nothing more damaging than being told, ‘I love you—but not really.’”

He sees echoes of that rejection in the city’s silence. “If that’s the stance of families, it tells you what’s happening locally at the systemic level,” he said. “Benign neglect is still abuse.”

Even education systems, he says, are complicit. “One of the first books banned in Wicomico County Public Schools was about the gay experience,” he noted. “The book had never even been checked out. And still, it was pulled. That tells queer students they don’t have a future. They don’t exist in the world that’s being built around them.”

He bristles at the idea that some in local news media view LGBTQ+ issues as “too controversial” to be fully covered. “Controversial to who?” he asked. “Marginalized groups aren’t controversial to themselves. They’re only controversial when a dominating voice suppresses them and reframes them as fringe.”

Kyriacopoulos is also critical of what he calls the absurd notion that queer people must take the lead on efforts for inclusion while being simultaneously excluded. “It’s ridiculous on its face. If we keep suppressing people, how are they supposed to rise up? You’ve stripped them of opportunities to have a voice, and now you’re asking why they’re silent?” He emphasized that it is the responsibility of elected leaders to care for everyone and not burden already marginalized groups with additional tasking.

In his classroom, he pushes back on the very notion of normalcy. “‘Normal’ is just another piece of propaganda that’s been shoved down our throats,” he said. “Normativity is a tool of control, not a reflection of reality.”

He believes language matters, too. “Even the term ‘gay marriage’ is flawed,” he said. “It was never about gay marriage. It was about equal marriage. We need to question how we speak, because language frames what’s possible.”

Symbols, he argues, can’t fix everything, but they can open a door. “Just putting up a flag doesn’t solve structural injustice, but it starts by saying, ‘I see you.’ That may be the beginning. In the Jewish tradition, there’s always a seat at the table for Elijah. You may never show up, but there’s a place set. We need to create that space not just for queer folks, but also for women, for Black communities, for anyone being pushed aside.”

Even the idea of removing the rainbow crosswalk, he says, raises deeper philosophical and moral questions. “You’ve already erased it. So what are you going to replace it with?” he asked. “Because unless you’re prepared to offer something that meaningfully includes those who’ve been excluded, you’re just re-inscribing a discriminatory status quo.”

He draws a connection between city decisions and a broader retreat from human rights. “It’s debilitating to watch us devolve like this. Expanding who counts as a person should be the goal. But now we’re seeing the opposite, this shrinking of the circle of inclusion.”

That regression, he argues, says something damning about the community. “It’s not okay that a transgender child gets thrown out of their home. It’s not okay that the city removes signs of inclusion. We need a community that says: you are safe, you belong, you matter.”

Kyriacopoulos doesn’t just speak as an academic. He speaks as a father, and as a stakeholder in the local university. “Salisbury earned the [inclusive] recognition it once had,” he said. “It deserved it. But now we’re at a decision point. Do we keep going forward? Or do we begin again to deny people their right to exist?”

He acknowledges that there are healthy paths forward. “We are struggling,” he admitted. “But with support from parents and guardians, and other people who write the checks, we could function in a more meaningful way.”

Josh Hastings and the Politics of Possibility

“National dynamics play out in local ways.” - Josh Hastings, Wicomico County Councilman

Wicomico County Councilman Josh Hastings reputation as a “policy nerd” is self-evident. With a master’s degree in public policy and a deep background in conservation, agriculture, and rural issues, Hastings brings a systemic lens to his work on the Wicomico County Council. Now in his second term representing a district that includes the city of Salisbury, Hastings says his mission is about more than politics; it is about creating space for complexity.

“A lot of people tend to look at issues as black and white,” he said. “It’s either frozen or it’s on fire. My approach has always been about speaking at the 10,000-foot level—being clear about all the situations and issues at play, and helping the public make more wise and well-rounded decisions.”

That clarity, for Hastings, includes acknowledging that “national dynamics play out in local ways,” for a variety of issues.

Though he doesn’t represent the City of Salisbury itself, the city and county governments are distinct, Hastings affirms himself as a visible and vocal ally in broader conversations about equity and inclusion. His posture is deliberately non-performative: he prefers listening over posturing, humility over headlines.

“As the old phrase goes, God gave you two ears and one mouth for a reason,” he said. “I always personally like to show up to listen and to actually understand issues from various perspectives and support those who say change needs to be made.”

Hastings sees allyship not as leadership, but as faithful accompaniment. He adheres to a servant leadership model that centers marginalized communities, often asking directly: How can I help? Where can we bring extra attention? How can I raise your voice?

“I support those who are leading and try to figure out where I can be helpful. I don’t see my job as taking credit for the work of the community. My job is to help the community figure out how we lift up others.”

Still, he’s realistic about the structural limitations of the County Council itself, especially compared to jurisdictions like Frederick County, where leaders have passed broader equity and anti-discrimination legislation.

“As far as doing more things legislatively that other counties have the ability to do, we are not structured as a county to do those things,” he explained. “And I wish that structure would change. But until there is a change in power and leadership, that is not going to happen.”

In Wicomico County government, as in many local governments, he said, “discretion sits with whoever is the body’s president.” Even a well-crafted, thoughtful bill might never be publicly discussed by the body. “I could come up with anything I want as a bill as a legislator, and it may never see the light of day,” he shares.

Despite those constraints, Hastings insists that Wicomico County is, at its core, a welcoming place. “We may have certain people who have certain thoughts and views, but that is not the majority,” he said. “I think Salisbury and Wicomico County are very much a welcoming community—more than others.”

At the same time, he doesn’t minimize the pain many LGBTQ+ residents feel, or the reality that some still experience government as a source of exclusion rather than support. “I’m cognizant of the fact that there are a lot of folks that feel excluded and that feel hurt,” he said. “I don’t think government should be used as a tool to hurt others or to exclude people—but it often is.”

Consciously identifying as white heterosexual, Hastings feels a personal stake in making the county a place where all diversity can thrive. But he’s careful not to conflate his experience with others’ nor to seek credit.

“I want people to know they are loved and appreciated and welcome,” he said. “But I also want to see the country as a whole—and especially Salisbury and Wicomico County—become a more open and engaged society. I think we can do better. I think we will do better.”

While LGBTQ+ rights are part of that vision, Hastings also keeps the broader picture in view. Wicomico remains one of the most impoverished counties in Maryland, with serious challenges in housing, education, and healthcare. He points out how over 40 languages are now spoken in county schools, and he believes that growing diversity should be embraced and celebrated.

“We have a lot of folks who are really struggling,” he said. “At the end of the day, I just want people to have fairness and opportunity in the broadest terms.”

For Hastings, that means staying present, staying humble, and staying focused on the long game.

“Overall, this is a beautiful community,” he said. “And it’s going to continue to get better and better. We just need to make sure that it’s welcoming for everyone and that everyone has the ability to thrive here.”

Local Struggles, National Conversations

Salisbury’s rainbow crosswalk reflects a broader cultural and political moment in which symbols of LGBTQ+ visibility have become contested ground. From the Eastern Shore to Milwaukee, Wilton Manors to Leesburg, communities across the country are grappling with how public spaces reflect inclusion, safety, and belonging.

While Salisbury wrestles with its own crossroads other cities are making different choices. Some are investing in vibrant displays of identity and history as a form of resistance and affirmation. Others are pushing back against legal and political efforts to erase these expressions.

As local leaders, activists, and residents weigh their options, one message resonates clearly: visibility matters. It is not just about paint on pavement, but about the values communities choose to uphold and the futures they want to build together.